The British Museum’s new World of Stonehenge exhibition is a journey through prehistoric eras. The exhibition is not really about Stonehenge at all but about the world at the time.

So here’s a walk through the ages to accompany your journey through the exhibition and the amazing finds, making connections en route with how Stonehenge was developing over 1,000 years.

The story starts as the Ice Ages end, before 9,000 BC (11,000 years ago). It’s a vibrant world of Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) harpoon-wielding hunter-gatherers and shamanistic-style connections with nature.

a vibrant world of Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) harpoon-wielding hunter-gatherers and shamanistic-style connections with nature.

Meanwhile stone axes are beautifully crafted and exchanged across Europe. This is when the great wooden ‘totem’ poles are erected in the Stonehenge landscape. All that remains are the post holes …

As farming arrived in Britain by 4,000 BC, the early farmers of the Neolithic settled down. They cut down forests and created timber tools with hafted aesthetically gorgeous polished stone axes and they cultivated crops and domesticated animals, first sheep and goats and then cattle which enabled new technology of wheeled carts.

Pottery (heavy and fragile) became possible in the new settled communities. Their new ownership of lands and ceremonial ancestral lands were expressed in great earthen monuments (causewayed enclosures and cursus) which dominated the landscape of Salisbury Plain and elsewhere. Great tombs called Long Barrows and monumental chambered tombs held their collective ancestors (at least of certain families) but few grave goods. Orkney’s ‘stalled cairns’ first echoed the rectangular homes of the living and then, as houses became circular, rounded tombs appeared.

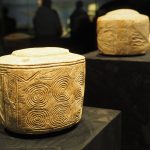

The spiralling rock art of the impressive Brú na Bóinne chambered tombs in Ireland and the mace-head of Knowth (3,500-3,000 BC) and others (eg. Maesmore, Wales) from around the Irish Sea reveal true artistry. The chalk drums from Yorkshire (3,000 BC) are remarkable and poignant items (even though we cannot know the complex art’s meaning) that accompanied children’s graves. On the continent, distinctive Neolithic art appears on the plaques in Portugal and Spain (3,500-2,750 BC).

Permanent settlements (such as stone-built Skara Brae in Orkney) and great tombs developed in varying styles and, from c.3,000 BC, the Late Neolithic social organisation enabled Stone Circles to be erected around Britain. While France’s Carnac built its great alignments of stones, Britain began erecting stone circles and would continue to do so for 1500 years until c.1,500 BC. And so the 110m diameter ditch and inner bank of Stonehenge was now dug with antlers and ox scapula shovels. The Pyramids of Egypt wouldn’t be built for another 400 years.

Soon the Bluestones, so carefully quarried and erected into a stone circle in the Preseli Hills in Wales, were moved , complete with cremated dead, to their new stone circle within Stonehenge’s ditch.

Pictorial art seems to have been taboo but rock art with cup marks, and zigzags and lozenge shapes and etched abstract shapes on rock and Grooved Ware pottery alike, were the art of the time across Britain and Ireland.

More Neolithic art from this time has been found at the ceremonial site of Ness of Brodgar in Orkney than everywhere else in Britain put together.

Enigmatic carved stone balls have been found across Scotland. And unique chalk plaques found near Stonehenge clearly have some message but what?

Flint continued to be the great tool kit for making blades as tools and as arrowheads. 400 flint mines were dug at Grimes Graves in Norfolk.

As the 7m high 20-ton Sarsen stones were dragged 20 miles and erected at Stonehenge in c.2,500 BC, a great settlement for builders from around Britain was built at nearby Durrington Walls. Here, midwinter feasting and celebratory hunting joined with processions from the wooden circles of the living to Stonehenge’s stone circle of the ancestors.

Meanwhile, the Copper Age, lasting a couple of hundred years, heralded the Early Bronze Age (c.2,500-1,600 BC). The innovative Beaker People arrived from c.2,475 BC with new ways and soon a central circle of Bluestones was erected within the Sarsens trilithon curves and monumental and mysterious Silbury Hill was built with vast manpower.

Durrington Walls fell out of use as a settlement, and was ceremoniously and monumentally sealed off by a ditch. New homes springing up on the far (west) side of Stonehenge and a small gold sun disk revealed how times had changed; small, portable items of awe were created instead of massive monuments now.

The shiny new metals of copper and bronze could be smelted and shaped in moulds into tools and weapons.The Beaker people had brought their new culture with singular burials with rich grave goods, copper and then bronze daggers. The Amesbury Archer, who had been brought up near the Alps, took it all with him when he was buried surrounded by his elite copper daggers, gold adornments, flint arrows, pottery, antler and boar tusk, oysters and more; buried in sight of Stonehenge, it is clear that the site was still held in awe.

Back on the continent, in Europe, this was the time of the Valcamonica stone (one of the first pieces to greet you in the exhibition); added to by generations in a place of worship, it celebrated the sun, gatherings of people, wild animals and farming. This was new pictorial art.

The old materials were still valued though; copper and tin were hard to find in some areas and in Denmark flint copies of metal axes (2,350-1,700 BC) were lovingly made and even exported to Britain and Ireland.

The old materials were still valued though; copper and tin were hard to find in some areas and in Denmark flint copies of metal axes (2,350-1,700 BC) were lovingly made and even exported to Britain and Ireland.

In c.2,280 BC. the Stonehenge Bluestones were rearranged to encircle the inner horseshoe of sarsen stones. Although adapted for their current beliefs and priorities, stone circles were still meaningful and important.

Occasionally, we are reminded that wooden circles were important too; the survival of Seahenge on the Norfolk shore is a marvel. Created in 2,049 BC, its upturned trunk at its centre and timbers closely guarding it in a circle, their bark side facing outwards, we sense the spiritual aspect of life, although we cannot know how the site was used.

Further adaptations of Stonehenge were made, while burial barrows popped up around the landscape. These contained ideas from abroad, French weapon styles, Baltic amber and Whitby jet while skillfully crafted ever-shining gold remained popular.

New ideas turned the old ways into antiques, seemingly imbued with special properties; the local seer (or metalworker)’s burial (c.2,100-1,800 BC) included already millennium-old polished stone axes.

From c.2,000 BC, shining gold, gleaming amber from the Baltic (like the Knowes of Trotty burial necklace or the Hove cup 1,750-1,550 BC) and elite bronze (made with copper and rare tin) became conspicuous consumption. The bronze was made with tin and copper (the Great Orme mines ran for miles); the gold – often Cornish gold – glittered with sun symbolism.

Across NW Europe, lunulae, crescent-shaped collars, were made of dramatically thin gold, often from that Cornish gold.

And it’s fascinating to think that, when Stonehenge region’s Bush Barrow’s gold lozenge (1,950-1700 BC) or the stunning Mold Cape was crafted in Wales, or the Rillaton cup of Cornwall, it would still be 200-300 years before Tutankhamun was buried in his gold mask.

In the Middle Bronze Age (1,600-1,200 BC), a final touch was added to the Stonehenge stones: daggers and axes were carved into the already ancient trilithons of Stonehenge. A carved stone in a Dorset grave of 2,000-1,500 BC echoes these engravings.

Great barrow cemeteries were fashionable now and built up around Stonehenge, and cremation burials too hid great wealth under the soil, as did a remarkable buried hoard of necklaces, bracelets and tools (1,400-1,250 BC).

Mythologies of the sun were apparent in Denmark (where fish, birds, horses and snakes propelled the sun on its boat-carried way) and through W.Europe as well as Britain. And shining gold was the obvious material to use to propitiate and represent the bright sun. It was shaped into stunning cone hats in Germany and France, model (solar?) boats in Denmark and gold belts as votive offerings.

Shipwrecks off Dover carried copper and tin (raw and as weapons and tools) across the Channel. And the Nebra Sky Disc of 1,600 BC was made in Germany using Cornish gold and tin. Britain and the continent were well connected …

But it wasn’t a time of peace. Bronze made dedicated weapons of war. While one workshop’s over-sized armour for votive offerings reached England, France and the Netherlands, the Nebra Sky Disc was accompanied by magnificent swords as magnificent bronze battle shields and spears spread.

As the Late Bronze Age dawned in c.1,200 BC, it was the time of the legendary Trojan War, far away in modern Turkey. Bronze armour and shields clashed in real and violent war in northern Europe and some armour and weapons were deposited as votive offerings, just as wooden figures were (Roos Carr 1,100-500 BC).

Gold remained attractive. The hefty gold collars (gorgets) from Ireland (800-700 BC) show that gold craftmanship had not been forgotten.

As the hard Iron Age would now begin to depose bronze from its dominance, the world of Stonehenge moved into the past. It was now an embattled age far removed from monumental stone circles, flint and focus on the sun. It forged weapons and strong leaders feasting from great bronze cauldrons (Battersea Cauldron 800-600 BC). But still the glint of gold shone a ray of sunshine from items like the Shropshire bulla (c.1,000-800 BC).

The exhibition shares with us a remarkable collection of stunning items set out in themes of connections around the ancient world, the people and DNA, the links, technologies and crafts, and the symbolism.

I hope this blog has helped you to match the displayed finds with the timeline of the development of the amazing Stonehenge site as it developed over those thousands of years.

The work of Gillian Hovell BA(Hons), ‘The Muddy Archaeologist’, ranges from prehistory into the Classical world, through archaeology and ancient history in-person, online, in the media, in publications and in the field, and can be viewed at www.muddyarchaeologist.co.uk.

Her ever-growing online courses can be found at https://www.muddyarchaeologist.thinkific.com

a vibrant world of Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) harpoon-wielding hunter-gatherers and shamanistic-style connections with nature.

a vibrant world of Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) harpoon-wielding hunter-gatherers and shamanistic-style connections with nature.

The old materials were still valued though; copper and tin were hard to find in some areas and in Denmark flint copies of metal axes (2,350-1,700 BC) were lovingly made and even exported to Britain and Ireland.

The old materials were still valued though; copper and tin were hard to find in some areas and in Denmark flint copies of metal axes (2,350-1,700 BC) were lovingly made and even exported to Britain and Ireland.